Anatomy of a Horse – Skeleton, Muscles, Organs and Their Functions

The anatomy of a horse is both fascinating and complex. From the skeleton to the muscles, from the digestive to the respiratory organs – each system plays a vital role in health and performance. In this article, you will learn everything about the body parts of a horse and its function, common health issues, and how to optimally support your horse with targeted training, proper nutrition, and daily care.

Inhaltsverzeichnis

➡️ Must-Watch: Getting to Know Horses with David O’Connor – Horse Anatomy

Discover how your horse’s anatomy mirrors your own! David O’Connor reveals fascinating parallels—like why a horse’s leg functions like a human hand—and explains how this understanding can enhance your riding, training, and care.

Skeletal Anatomy of a Horse

The skeletal anatomy of a horse forms the solid foundation of the body, providing support, protection, and mobility. It consists of around 205 bones, which are connected by joints, tendons, and ligaments. This structure gives the horse high resilience and flexibility – crucial for a flight animal.

How many bones does a horse have?

An adult horse has approximately 205 bones, although this number can vary slightly depending on the breed and individual differences. Especially important are the weight-bearing horse leg bones, the spine, and the joints – all essential for movement and balance.

Bones of the Horse Skull

The skull protects the brain, holds the sensory organs, and allows for food intake. Most bones of the horse skull are firmly fused, except for the lower jaw, which remains movable for chewing

Horse Spine and Thorax

The spine is the central axis of the horse’s body and consists of around 54 vertebrae. It ensures stability, flexibility, and transmits power between the front and hindquarters. The horse anatomy bones of the spine are divided into different regions:

The thoracic area – or thorax – protects vital internal horse anatomy organs and is composed of 18 pairs of ribs and the sternum. While stable enough to carry the upper body weight, it is also flexible to allow breathing.

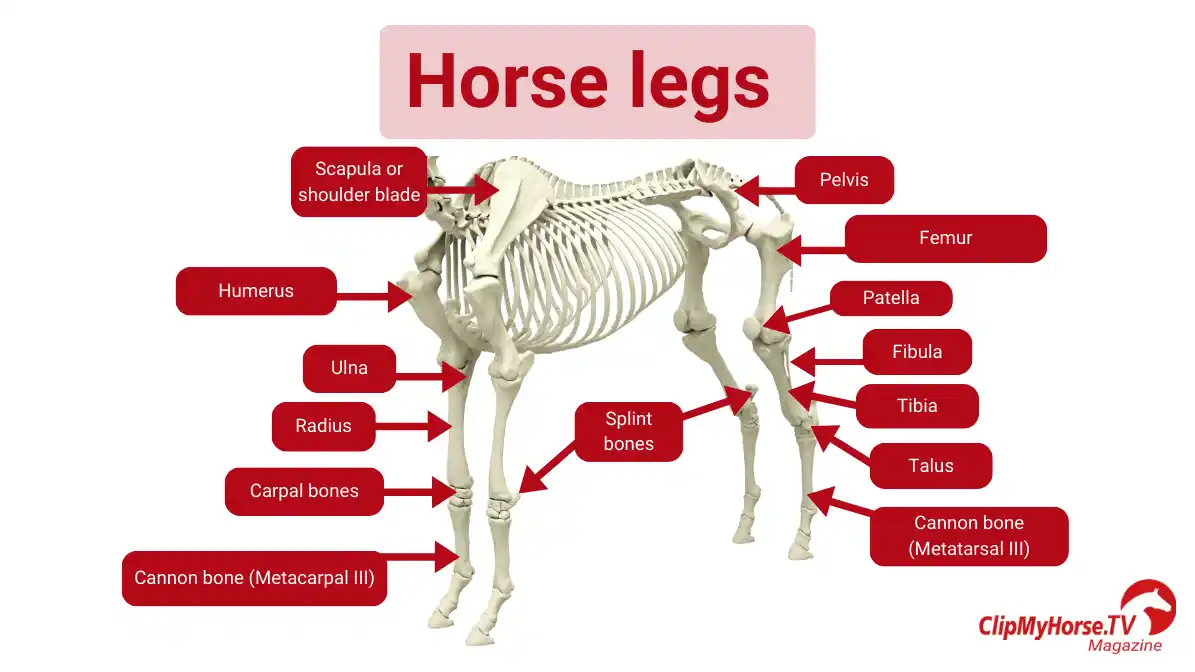

Anatomy of a Horse Leg – Forelimbs

The anatomy of a horse leg, especially the front limbs, is designed for shock absorption and weight-bearing. Unlike humans, horses do not have a collarbone – their horse leg bones are attached to the torso only via muscles, tendons, and ligaments, allowing greater flexibility and shock absorption.

Anatomy of a horse leg – Hind Limbs

The hind limbs are responsible for propulsion and force transmission. They are firmly connected to the spine via the pelvis, making them essential for performance.

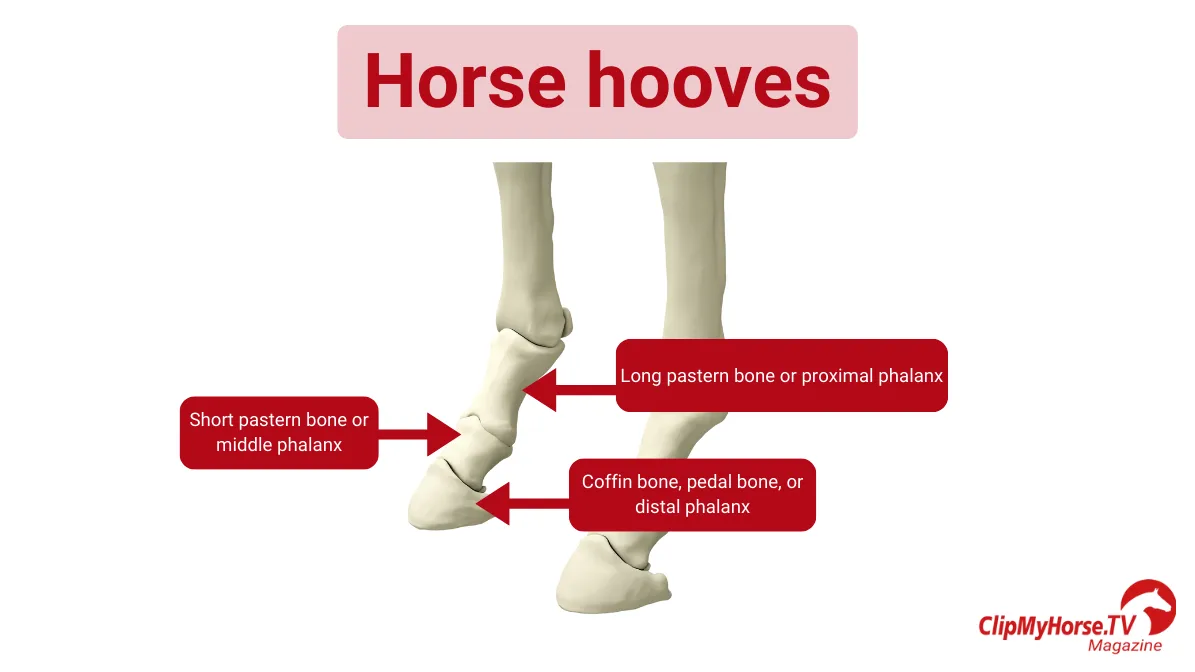

Anatomy of a Horse Hoof

The anatomy of a horse hoof is designed to carry the horse’s entire body weight and absorb impact with every step.

The hoof is a sensitive yet resilient structure. A healthy horse hoof is vital for soundness and performance.

Horse Muscles – The Musculoskeletal System

The horse anatomy consists of two major systems responsible for motion:

- The passive musculoskeletal system, made up of bones, joints, ligaments, and tendons

- The active musculoskeletal system, composed of the muscle anatomy of a horse

Both systems work together to enable movement, maintain posture, and ensure overall performance. Poor training, overloading, or incorrect care can lead to issues like lameness, joint disease, or muscular imbalances.

Passive Musculoskeletal System

This includes the horse bones, joints, ligaments, and tendons. Joints connect bones and are supported by cartilage and joint fluid to reduce friction and allow smooth motion.

Joints of the Horse

Joints connect bones and allow for movement. They are lined with cartilage and filled with synovial fluid to minimize friction and ensure smooth motion.

Horse Tendons and Ligaments

Tendons and ligaments play a central role in the anatomy of a horse leg, stabilizing the limbs and transmitting movement. Tendons connect muscles to bones, transferring force, while ligaments connect bones to one another, ensuring joint stability.

Bowed Tendon in Horses

A bowed tendon horse injury usually affects the flexor tendons and occurs from overstrain or misalignment. It can lead to swelling, pain, and long recovery times.

Suspensory Ligament Injury in Horses

The suspensory ligament is one of the most important ligaments in the horse’s leg, as it supports the fetlock joint and protects it from overload. If overstressed or injured, it can lead to a suspensory ligament injury.

Horse Muscles

The horse muscles make up the active musculoskeletal system, generating movement and supporting posture. Horses have over 700 muscles, divided into three main regions:

- Forehand muscles (shoulders, neck, chest)

- Trunk and back muscles (support the rider, maintain posture)

- Hindquarter muscles (generate forward motion and thrust)

Balance Between Flexors and Extensors

- Flexors pull limbs inward, support collection and posture.

- Extensors push the limbs outward, enable forward motion and power.

Muscle Building in Horses – Done Right

Building up horse muscles effectively requires a smart mix of training, rest, and nutrition:

- Gradual progression: Increase workload slowly

- Varied workouts: Include dressage, pole work, trail rides

- Daily movement: Maintains strength and joint health

- Warm-up and cool-down: Essential to prevent injuries

➡️ Must-Watch: Muscle Development – Training and Feeding Combined

Dr. Patricia Sitzenstock explains which nutrients are essential for muscle growth and how feeding and training go hand in hand.

Training Plan for a Healthy Musculoskeletal System

A good training plan prevents injury and builds resilience. Make sure to incorporate variation, strength work, and recovery phases.

Internal Organs Horse

The internal horse anatomy organs are essential for overall health, performance, and well-being. They regulate digestion, circulation, respiration, and metabolism. A solid understanding of horse anatomy and physiology helps detect diseases early, optimize feeding, and adjust training accordingly.

Digestive System – How Horses Process Food

The digestive anatomy of a horse is designed for continuous intake of fiber-rich forage. Since horses can’t consume large meals at once, small and frequent feedings are key.

Which organs are on the left side of a horse?

- Stomach – small and non-expandable

- Spleen – stores and regulates red blood cells

- Cecum and large intestine – ferment fiber through microbes

Common Digestive Disorders in Horses

- Colic – One of the most dangerous equine disorders. Triggered by sudden diet changes, stress, dehydration, or low forage. Symptoms include restlessness, pawing, rolling, and lack of appetite.

- Gastric ulcers – Caused by long fasting periods or excess concentrates. Signs include weight loss, frequent yawning, and lethargy.

- Diarrhea – Can result from poor feed quality, parasites, or stress.

- Constipation and fermentation issues – Often due to low movement, water deficit, or unsuitable feed (e.g., excess straw or grass).

➡️ Must-Watch: Gastric Ulcers in Horses – Causes, Symptoms, and Diagnosis

Dr. Nimet Browne explains the types, causes, and subtle signs of this common but often overlooked condition—and how to take preventive steps to protect your horse’s health.

Feeding – The Basis for Healthy Digestion

A horse’s digestion relies on continuous access to roughage. High-quality forage promotes:

- Chewing and saliva production

- Stomach lining protection

- Gut flora balance

- Smooth digestion flow

Respiratory System

The respiratory anatomy of a horse diagram reveals an extremely efficient oxygen intake system. A horse’s lungs have a surface area of about ten tennis courts and are among the most powerful in the animal kingdom – but also quite sensitive.

Facts and Figures

- A 500kg horse has a lung volume of 40–55 liters

- Around 90,000 liters of air pass through daily

- Resting respiration: 8–16 breaths/minute

- Under exertion: up to 150 breaths/minute

Cardiovascular System

The cardiovascular system delivers oxygen and nutrients while removing waste. It's also key for temperature regulation and performance.

Facts about the Horse’s Heart and Circulation

- The average heart weighs 3.5–4.5 kg (up to 10 kg in racehorses)

- Resting heart rate: 28–44 bpm; peak: up to 250 bpm

- Blood volume: ~7% of body weight (≈35L in a 500kg horse)

- The spleen can release extra red blood cells during intense effort

Excretory System

The excretory system is responsible for eliminating toxins and regulating the body’s water balance. It includes the kidneys, liver, and bladder – essential components in horse anatomy and physiology.

Key Facts

- Horse kidneys filter about 50 liters of blood daily

- Horses are highly efficient at water retention for digestion and cooling

- Their urine often appears cloudy due to high calcium levels – this is normal

Horse Teeth

The Horse teeth are specialized for grinding fibrous food. They grow continuously and must wear down evenly through chewing. Regular dental checks are crucial for health and feed efficiency.

How many teeth does a horse have?

- Stallions and geldings: 40–44 teeth

- Mares: 36–40 teeth

Teeth grow throughout life and require regular floating to prevent sharp edges and malocclusions.

Horse Age by the Teeth Chart

Tooth wear can vary based on diet, genetics, and environment, so this chart provides an estimate, not an exact measure. Always consult an equine dentist for precise evaluations.

Nervous System – Control Center of the Body

The horse anatomy includes a highly responsive nervous system that controls movement, sensory input, reflexes, and behavior. It's split into:

- Central nervous system (CNS) – brain and spinal cord

- Peripheral nervous system (PNS) – all nerves outside the CNS

Although the horse’s brain is relatively small, it learns quickly and responds sensitively to signals and stimuli.

Sensory Organs Horse

Horses, as prey animals, have highly developed sensory systems to detect their environment early.

Conclusion – Understanding Horse Anatomy

The horse is a strong, adaptable, and sensitive animal. Its anatomy is built for efficient movement, digestion, and perception. A deeper understanding of horse anatomy helps you train, feed, and care for your horse in a way that prevents injury and supports long-term health.

Key takeaways:

- Horse bones and musculoskeletal systems ensure stability and movement

- Digestive systems are optimized for fiber-rich forage – poor feeding can cause colic or ulcers

- Lungs and circulation support performance but need careful management

- Senses and the nervous system enable subtle communication and quick responses

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) – Horse Anatomy

Which organs are located on the left side of a horse?

On the left side, you'll find parts of the stomach, the small intestine, the left lung, and significant sections of the large intestine, including the cecum.

What promotes muscle growth in horses?

Targeted training, a protein-rich diet with high-quality amino acids, and sufficient recovery periods are essential for developing horse muscles.

What are symptoms of PSSM2 in horses?

Horses with PSSM2 often show muscle weakness, stiffness, rapid fatigue, and sometimes trembling or muscle atrophy, especially after exercise.

How can you build muscles in an older horse?

Low-impact training, targeted gymnastic exercises, uphill walking, and a protein-rich, senior-appropriate diet can slow or reverse muscle loss.

How can a horse gain muscle quickly?

A combination of regular, varied training (e.g., groundwork, pole work, hill training) and a balanced, protein-rich diet effectively promotes muscle growth.

What helps a horse with PSSM2?

A low-starch, low-sugar diet with added amino acids and a carefully tailored exercise program help relieve symptoms and support muscle development.

How long does it take to build muscle in a horse?

Visible changes can appear after 6–8 weeks, but sustainable muscle building usually takes several months to a year.

Can a skinny horse build muscle?

Yes, but it must first reach a healthy body condition through balanced nutrition. Then, targeted training can strengthen the musculature.

What is the best way to build muscle in a horse?

Through diverse training with specific exercises, a high-protein diet, and proper recovery phases, muscle development can be optimized.

How often should a horse exercise when building muscle?

Three to five focused training sessions per week, with rest days in between, are ideal for effective muscle growth.

Why isn't my horse gaining muscle?

Possible reasons include poor nutrition, incorrect or insufficient training, medical issues such as PSSM or gastric ulcers, or too little recovery time.

How do I train the trapezius muscle in a horse?

Stretching exercises, pole work, lateral movements, and long-and-low riding activate and strengthen the trapezius muscle.

How many muscles does a horse have?

A horse has around 700 individual muscles, all contributing to movement, stability, and vital functions.

What nutrients support muscle building in horses?

High-quality proteins, essential amino acids like lysine, and omega-3 fatty acids are beneficial for muscle development.

How do I get my horse to build more muscle?

Through structured strength and gymnastic training along with a protein- and energy-rich diet, horse muscles can be significantly developed.

Which amino acids are important for horse muscle building?

Lysine, methionine, and threonine are key for protein metabolism and support effective muscle development.

What should I feed my horse to support muscle growth?

A well-balanced mix of forage, high-quality protein sources (e.g., alfalfa, flaxseed), and targeted amino acid supplements encourages muscle gain.

How can I build abdominal muscles in my horse?

Exercises like stretching, hill work, lateral movements, and groundwork strengthen the core muscles and support posture.

How long does it take for a horse to build muscle?

Muscle development is a long-term process, typically taking months. First results are usually visible after 6–8 weeks.

Can walking help a horse build muscle?

Yes, structured walk training (especially uphill), with poles and stretching, can improve muscle tone, especially in the back and core.

How do I recognize a well-muscled horse?

Good muscle symmetry, a strong topline, a rounded croup, and a well-developed back indicate healthy muscle structure.

What strengthens bones in horses?

A balanced diet with calcium, phosphorus, vitamin D, plus regular exercise and sunlight exposure supports healthy horse bones.

How many bones does a horse have?

A horse has approximately 205 bones, although the exact number may vary slightly between individuals.

How many teeth does a horse have?

Stallions and geldings typically have 40–44 teeth, while mares usually have 36–40, as their horse wolf teeth may not develop.

What soothes a horse’s stomach?

Continuous feeding of high-fiber forage like hay, along with mucosal-protective nutrients like lecithin and pectins, helps balance stomach acid.

How are gastric ulcers treated in horses?

With acid-reducing medication (e.g., omeprazole) and a diet of frequent small, low-starch meals to protect the gastric mucosa.

What does the spleen do in horses?

The spleen stores red blood cells and releases them during exertion to improve oxygen delivery.

How do you treat a swollen hock in a horse?

Initial steps include cooling, rest, anti-inflammatory treatments (bandaging or medication), and veterinary examination if swelling persists.